Sungchan Cho

Director, Hananuri Academy of Northeast Asian Studies

The need to escape from a disconnected space to be connected is such a natural human need that requires no proof just as the axiom in mathematics. Throughout the long history of mankind, some have embodied this need as a desire for territorial expansion, while others have materialized it through the exchange of civilization in such forms as the “Silk Road.” Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has convincingly revealed the reality of how closely the world is connected. Still, there remains a place that is yet to be connected. It is South Korea. North and South Korea are separated by the Military Demarcation Line, obstructing land routes from the South not just to the North but also to the Asian and European continents. Although South Korea sits on one periphery of the Asian continent, it is still an island in a geopolitical sense.

The world map produced from a Korea-centric perspective would place the entire Korean Peninsula including South Korea as the central nation in Northeast Asia. When upside down, however, the map transforms it into a peripheral state. Shin Young-bok (2012) paid attention to the creative possibility of the periphery. He said the periphery is a space of change, of creation, and of life. Shin perceived that the peripheral consciousness offers an insight into the world and the social agents, thus breaking the frame we are locked up in and creating a sheer escape in search of new territory.

South Korea is on the periphery of the continents of Asia and Europe; and in a geopolitical sense, it is an island. It is where the maritime and the continental forces meet, and where the two Koreas remain in conflict over ideology. However, if the history of the Korean Peninsula can paradoxically suggest an insight into the world and the social agents, and if it can generate a dynamic energy for the search of a new territory, the painful history of the peninsula could be endured with gratitude.

Then, how can it be connected? A measure in the perspective of the policy studies may sound fairly prosaic. But the term would gain vitality when a persuasive measure is closely connected to our dream. As one of the measures, I would like to present the Northeast Asian Peace and Economy Cooperation Model based on the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE-based NAPEC Model). This paper consists of three sections. First, it compares Ahn Jung-geun’s theory of Oriental Peace with the history of European integration, followed by a review of the Northeast Asia Peace and Economic Cooperation Model that has been promoted by the United Nations (UN) and other related international organizations. As a practical strategy for the model, the paper discusses the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE), a strategy adopted by the UN to achieve its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The last section considers what role Jeju, “the island of peace,” can play in the peripheral area.

Ahn Jung-geun’s Theory of Oriental Peace and EU, and the NAPEC Model

The year 2020 marks the 110th anniversary of the execution of Ahn Jung-geun, a Korean patriot who sacrificed his life for national independence. On Oct. 26, 1909, Ahn, a special general for the national independence of the Korean Army, fatally sniped Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi at the Harbin railway station in the jurisdiction of Russia. During the five months of imprisonment following his arrest and until his execution on March 26, 1910, Ahn left significant documents concerning peace in Northeast Asia. The representative documents include The Affidavit (written in Japanese) and The Theory of Oriental Peace (written in Chinese). The Affidavit is a record of Ahn’s interview with Higher Court Head Yoshito Hiraishi on Feb. 17, 1910, the third day after the ruling on his capital sentence. Ahn wrote The Theory of Oriental Peace, which contains his opinions about the world of peace, and he worked on it until he was executed. As the request to postpone his execution was rejected, The Theory of Oriental Peace is Ahn’s incomplete posthumously published work. Fortunately, The Affidavit allows for an understanding of the key message that Ahn intended to present in The Theory of Oriental Peace.

The peace that Ahn advocates for is fundamentally different from the Western concept of peace or pax. The Latin term pax refers to the dominance of a strong party or the hegemony of an empire, while Ahn’s peace implies coexistence and mutual prosperity of the strong and the weak. To achieve Oriental Peace, Ahn suggested the creation of an economic community named the Oriental Peace Association. This approach contrasts with Ito’s theory of peace in the Far East as he implemented the strategy of imperial domination based on military power. Ahn’s peace theory aimed at logically and systematically refuting Ito’s theory. Surprisingly, Ahn’s theory is substantially analogous to the European integration model represented by the EU, thus bearing great significance for peace in Northeast Asia.

Through the two relatively short documents, Ahn expressed his idea of Oriental Peace, which he contemplated for a long time, according to his special commentary. First, The Theory of Oriental Peace suggests the background of Eastern philosophy as well as the reasons for punishing Ito. However, the unfinished writing failed to contain the essential part, the specific measures for Oriental Peace. As earlier mentioned, The Affidavit details the core of Ahn’s theory of Oriental Peace. To briefly introduce his suggestions, the ownership of a territory is unchangeable and Japan was supposed to return to China the ownership of Dalian and Lushun, which Japan had occupied after winning the Sino-Japanese War. Ahn suggested the restored regions should be at the center of realizing Oriental Peace, particularly between Korea, China, and Japan. To this end, competent people of the three nations could convene to form an internationally recognized economic community named the Oriental Peace Association. According to Ahn, the association would recruit individual members and collect 1 yen per person for membership to secure financial stability. He then wrote that a bank should be established to issue currency shared by the three nations. Additionally, important spots in the region should be deemed peace zones, where the bank would have a branch office to solve financial issues. Ahn said this would complete Oriental Peace, but to counteract against the world powers, representatives from the three nations would take responsibility for forming a military and organizing a corps of young men. Ahn figured that letting the young soldiers learn each other’s languages would strengthen brotherhood among the nations. Lastly, if the emperors of Japan, Qing, and Korea were crowned after making an oath to the Roman Catholic Pope — the Roman Catholic population accounted for two-thirds of the religious population at the time — Ahn presumed that the three nations could gain the trust of the people of the world and form even stronger forces. Although it reveals limits in certain aspects, such as making an oath to the pope, Ahn’s theory of Oriental Peace is still greatly insightful in that it presents specific strategies for peace in Northeast Asia.

Ahn’s argument was fairly innovative at the time but rather difficult to accept. However, his idea is very convincing because the core of his argument was actually realized in the progression of the EU.

The history of European integration is largely divided into three dimensions: the background of the times, the symbolic region, and the structure of integration. First, the background of the times features the horrible experience of World War I and World War Ⅱ. The pain caused by the two World Wars drove the creation of the EU of today. The next dimension should be Alsace-Lorraine, which has now become the symbolic region of European integration. Strasbourg, a central city of Alsace-Lorraine, is a border area between France and Germany, providing a cause for inter-state conflicts. Today, the European Parliament sits in the city, transforming Alsace-Lorraine into the symbol of reconciliation and peace. The last dimension is the realistic model for the structure of integration. However it may sound familiar now, the EU was actually formed through a long and complicated process. On May 9, 1950, French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman announced the Schuman Declaration, launching the European Coal and Steel Community. Later in 1993, the EU was established based on the Maastricht Treaty, leading to the creation of a single market, the establishment of the European Central Bank, and the introduction of a single currency.

It is natural that the similarity between the philosophy and the orientation of two different items leads to a similarity in their components. The same applies to Ahn’s theory of Oriental Peace and today’s EU. The commonality of the two systems in terms of goals can be summarized as “a warless status of peace and mutual prosperity.” The two ideas are also very similar in terms of the overall system, particularly for the creation of the central bank, the issuance of a single currency, and the use of an official language. However, differences are also found in terms of territoriality, characteristics of the economic communities, fundraising methods, and joint defense systems. Additionally, the two ideas exhibit a marked difference in winning international approval.

The European integration model presents a new hope and practicability to the members of Northeast Asia that have been trapped in devastating conflicts over a long period of time. Northeast Asia can also pursue a model similar to the EU. First, I would like to suggest naming it the NAPEC, which stands for the Northeast Asian Peace and Economy Corporation. The name reveals the target region and the goal of the community. The target region includes Northeast Asian states. Generally, Northeast Asia includes South Korea, North Korea, China, Japan, Mongolia, and Russia. The goal is to pursue peace and mutual economic prosperity. Northeast Asia is where war continues though fighting has ceased, thus it is in desperate need for peace more than in any other region on earth. Only when peace is settled, the regional economy can create a virtuous cycle and allow for mutual economic prosperity between neighboring states. The political characteristics of the concept is a “corporation,” which may sound ambiguous. Presumably, the concept I suggest will serve as an interim stage. Just as the EU has had controversy over whether or not to move onto the next stage of the European Federation, if the “corporation” I suggest is well operated, it could function as an interim stage before the creation of the Northeast Asian Union.

To create and develop the NAPEC, a diversity of economic communities should be established. As shown in the Moon Jae-in administration’s initiatives for the East Asia Railway Community, the Northeast Asia Energy Corporation, the Northeast Asia Logistics Community, and the Northeast Asian Atomic Energy Community, it is necessary to form communities with specific orientations. The former European Steel and Coal Community, the European Economic Community, and the European Atomic Energy Community were incorporated into the European Community and then remodeled as the European Union. In the same manner, the NAPEC can start by incorporating small-scale economic communities and develop into next-level political and economic communities. Should the larger scale incorporation be realized, more ideas could be adopted from Ahn’s theory of Oriental Peace, including establishing a central bank, issuing a single currency, allowing for a visa-exempt and tariff-exempt transportation of people and goods while recognizing national borders, and creating a joint defense force at a Northeast Asian level. It would be appropriate to use the language of all member states as official languages, rather than selecting a specific language.

UN’s Northeast Asia Peace and Economic Cooperation Model

There may be some readers who consider my idea an unreachable dream. However, it might not conclusively appear as an unrealistic idea when we review what happened and is happening in the Tumen River area, a border area between North Korea, China, and Russia.

In 1991, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) took on the Tumen River Area Development Programme (TRADP). The TRADP was the first project for economic cooperation and the first plan for sub-regional cooperation in Northeast Asia. The multilateral project involved five countries including South Korea, North Korea, Mongolia, and Russia, and the state that most actively engaged in the project was China. In 1992, China designated the Border Economic Cooperation Zone in Hunchun City, a border area near North Korea and Russia. It is China’s only economic cooperation zone in the border area, with three districts included for export-oriented processing, visa-exempt transnational commerce, and for trade with Russia and North Korea. The North Korean city that is connected to this zone is Rajin-Sonbong (or Rason). North Korea also showed a strong will for participation in TRADP by designating the Rajin-Sonbong Special Economic Zone in December 1991. However, TRADP was suspended due to Pyongyang’s withdrawal after its nuclear test. Several years later in 2005, Chinese President Hu Jintao expressed an intention to resume TRADP by scaling it up to the Great Tumen Initiative (GTI). GTI targets a vast area that encompasses Rason of North Korea, the three north provinces of China, and a part of the Primorsky Krai of Russia. Unfortunately, Pyongyang also withdrew from GTI in 2009, and the initiative is virtually on hiatus due to the intricate interests of participating states.

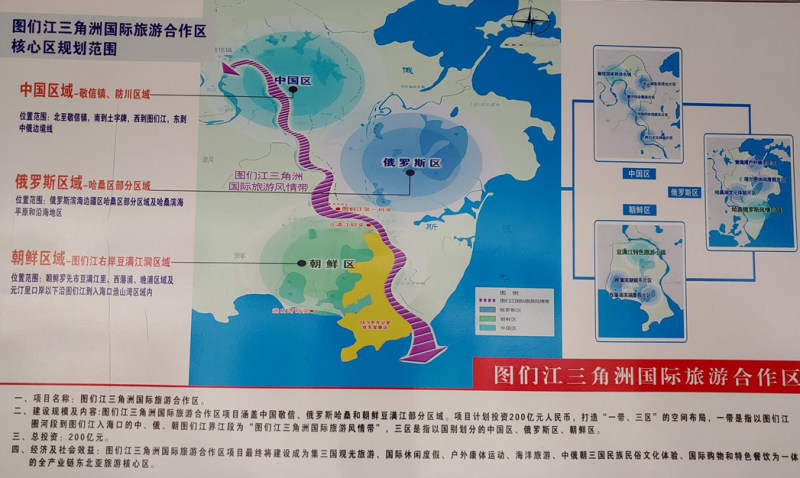

Despite the cessation of the GTI, the China-led experiment to create a Northeast Asian economic cooperation community is now being pursued in a different form. Currently, tourism is excluded from the UN’s economic sanctions against North Korea. Taking this advantage, China is working to construct with Russia and North Korea the Tumen River Delta International Tourism Cooperation Zone in the border area along the Tumen River. The initiative is aimed at creating a virtually “borderless” space for profits from shared tourism resources by establishing an international tourism cooperation zone with an area of 100㎢, which covers Fungchuan in China’s Hunchun, Dumangang Village in North Korea’s Rason City, and Khasan of Russia’s Primorsky Krai. According to the initiative, the zone will allow for visa-exempt entry and tariff-free commerce for up to 72 hours. What Ahn Jung-geun suggested in his theory of Oriental Peace is to be realized in this zone. Of course, since it is led by China, the South Korean government should make clear responses.

<Image> Development Initiative for the Tumen River Delta International Tourism Cooperation Zone

Source: November 2019, The author’s photo from the Fungchuan Observation Tower in Hunchun

UN selects Social and Solidarity Economy as an SDG strategy

Social economy (économie sociale in French), which has a 200-year history in France, was specified in South Korea by the enforcement of the Social Enterprise Promotion Act in 2007 and the Framework Act on Cooperatives in 2012. During the 2010 local election, social economy also emerged as a regional development strategy. (Jang 2018) The term is now firmly established as a common expression not just in Europe but also in South Korea. Jeju Island is one of the regions where social economy is actively practiced.

In late 1981, the expression of économie sociale was first stipulated in French statutes. Then on July 31, 2014, French President François Hollande led the enactment of the Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) by adding the term “solidarity.” The French legislation of the Law on SSE was due to the shortage in platforms for social economy. Noticeably, only four types of groups were legally recognized as social economic organizations, including cooperative unions, mutual aid cooperatives, associations, and foundations. In fact, social economy involves a range of areas and engages in literally all fields of society. Evidently, the former category shows that social economy could not be limited to a certain organization or territory. (Jeantet 2019) The organizations under the current Law on SSE also include social enterprises. Nonetheless, the Law still has its limits because the concept of SSE incorporates all of the organizations that pursue social values. The attempt to overcome this limit has recently become visible mainly by the UN.

Experts in France, who led the enactment of the Law on SSE, joined the team of UN agencies to explore the possibility of SSE. SSE also considers environmental issues and sustainability in addition to its existing awareness of the issues discussed with the theme of social economy. The International Labor Organization (ILO), the International Federation of Cooperatives (ICA), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the UN-affiliated Inclusive Social Development Division (DISD) have actively participated in exploring the possibility of SSE platforms.

It is well known that the UN, which is exploring the possibility of SSE platforms, is leading the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) project (2016-2030). SDGs are a common goal with a very high level of international consensus, as they were unanimously established by the 193 UN member states at the 70th UN General Assembly and at the UN Summit in 2015. Interestingly, at the same time, international organizations supporting the internationalization of SSE gathered in New York on Sept. 29, 2015, to commemorate the 70th UN General Assembly. They adopted the Declaration of the International Leading Group on Social and Solidarity Economy, and made it clear that SSE is a strategic means of implementing the SDGs. SDGs and SSE are two sides of the same coin.

Surprisingly, Cuba has also paid attention to the possibility of SSE. Cuba enacted the Act on Cooperatives in 2012 and made SSE a new economic development strategy. Professor Rafael Betancourt at Havana University, who also works on the Red ESORSE, aims to create a new social relationship that constitutes social economy that is centered not on the reproduction of capital but on life, going beyond the concept of organization (Betancourt 2019). If Cuba’s new attempt is successful, it could have great implications for the North’s transition in its economic system.

The increasing connectivity between SDGs and SSE with the support of the UN has expanded the possibility of cooperation with North Korea. North Korea has worked to achieve four major goals: food and nutrition security, social development services, resilience and sustainability, and data and development management (Choi 2019). Therefore, with the continued economic sanctions against North Korea, the strategy of pursuing SDGs at an international level through SSE could help open the door for exchanges and cooperation with the North.

Given the current trend where the UN internationalizes SSE as a measure to implement the SDGs, it is clear why South Korea’s non-profit organizations and local governments that pursue various humanitarian assistance and development cooperation projects with North Korea should choose SSE platforms. Furthermore, SSE has great significance as a theoretical framework for the shift of North Korea’s socialist economic system.

Jeju, shouting for peace from the periphery

The above review of two trends that have developed around the UN shows that our task is to embody SSE that the UN has chosen as the SDGs promotion strategy as a practical strategy for the NAPEC Model. Above all, it needs to be applied as a regional development strategy for the border area between North Korea, China, and Russia or a strategy for North Korean regional development.

To this end, the first step is to redefine the concept of SSE from the perspective of the NAPEC. In other words, based on the theory of commons that values land and currency, SSE can be redefined as the development of business activities with the philosophy of social solidarity by various organizations in the land that is the most basic of the real economy and in the economic space created by the highest currency. In this context, I have conducted a study on Jeju Island (in 2016 and 2019) with the privatization of commons as the core concepts.

Jeju Island is the land of possibility for SSE-based NAPEC. Ideological conflicts were sharply expressed during Jeju 4·3 but today it is shouting for peace in just the same way that Alsace-Lorraine does. Jeju Island has also played an important role in inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation. For example, it sent tangerines to North Korea from 1999 to 2010. It also launched a project to cooperate with the North using carrots and black pigs. The cooperation project was suspended from 2010 during the Lee Myung-bak administration, but Jeju resumed the project and sent 200 tons of tangerines to the North in 2018. Additionally, Jeju has established social economy as an important sector, so it can play an important role in future inter-Korean exchanges and cooperation. The North has recently announced that it will not receive free humanitarian aid under its national policy. A new approach is needed. At this point, exchanges and cooperation through SSE and regional development in North Korea can be promoted as international cooperation while respecting Pyongyang’s principle of self-reliance. I expect that Jeju Island can play an important role in this regard.

I would like to propose to Jeju, an island of peace, exchange, and cooperation. Hananuri, the institute where I belong, has carried out a project of supporting cooperative farms in North Korea’s Rason since 2009. Hanaruri has recently promoted a financially self-sufficient village project based on social and solidarity finance. The project remains a village-level financing institute called the “village fund.” If conditions permit, however, it is necessary to develop it into an urban regional cooperation project through social and solidarity finance at the Rason City level. Therefore, Jeju and Rason, both being special administrative districts of Korea and located at the northern and the southern ends of the Korean Peninsula, can become partners to establish a social and solidarity bank in Rason and to develop cooperative projects. These small practices will be the substantive start of SSE-based NAPEC.

Jeju is where the ideological conflict on the Korean Peninsula began. It is now time for the island to shout for practical peace from the periphery!

Dr. Sungchan Cho is the Director of Hananuri Academy of Northeast Asian Studies. He earned his Ph.D. at the Department of Land and Real Estate Management, Renmin University of China. He authored City of Coexistence (2015), Public Land Leasing Theory: Reforming the Land Policy in North Korea (2019), etc. and co-authored Land Reform Experience in China (2011, co-authored), Social Economy: An Inter-Korean Bridge (2020), etc. His papers include “Analytical Review of Jeju Free International City’s Development Strategy Depending on the Model of Privatizing Commons” (2016), “Comparative Analysis of Transition Route between China and North Korea’s Dual Land Ownership: Focusing on the Changes of Rural Land System” (2019), etc. He is currently conducting research on the theory of Social and Solidarity Economy, the inter-Korean urban cooperation model based on Social and Solidarity Finance, and the land system of Hong Kong (translation).