Park Chan-shik (Director of the Center for Jeju Historical Studies, Jeju Future Research Institute)

1. What are the archives of Jeju 4∙3?

The Archives of Jeju 4∙3 refers to all pertinent resources, including, but not limited to, text-based items, audiovisual items such as photographs and films, and artifacts associated with the people involved in the incident that have been documented and/or produced concerning the massacre of tens of thousands of residents during the armed clashes between the civilian armed forces and the state-led counterinsurgency forces which took place on Jeju Island, the Republic of Korea, from March 1, 1947, to Sept. 24, 1954, as well as the subsequent process of clarifying the truth related to the incident and restoring honor to the victims.

Jeju 4∙3 occurred on a small island of South Korea, which was then ruled at the time by the U.S. military amid the global-scale Cold War and the division of the Korean Peninsula after World War II. It was also the second most deadly incident in modern Korean history, the first being the Korean War. According to investigations, an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 people were killed out of the island’s then total population of 280,000. Nevertheless, the truth and justice had long been concealed as a detailed and comprehensive investigation of the truth had not been conducted until 50 years had passed since the historical event. In the process of democratization in Korea from the late 1980s, the fierce truth-finding movement of Jeju civil society, including survivors, students, civic groups, media, cultural circles, and academic circles, began to unfold, which in turn began to reveal the realities of the damage.

On Jan. 12, 2000, the long-awaited Special Act on Discovering the Truth of Jeju 4·3 and Restoring Honor to the Victims (“Jeju 4·3 Special Act”) was finally legislated, followed by the launch of the Committee on Discovering the Truth of Jeju 4·3 and Restoring Honor to the Victims (“Jeju 4·3 Committee”). The Jeju 4·3 Committee initiated a national-level investigation into the case, with the findings published in the Jeju April 3 Incident Investigation Report in 2003. After the announcement of the results, then President Roh Moo-hyun made an official apology during a visit to Jeju Island, expressing his “sincere apologies and words of consolation to the victims’ families and all the other Jeju residents for the past wrongdoings committed by state power.” Subsequently, the case went through a well-reasoned procedure of overcoming the past tragedies and moving toward the future, including the 2003 creation of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, the 2008 establishment of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, the 2012 national designation of April 3 as a national memorial day, and the 2013 official declaration of reconciliation between the Korean National Police Veterans Association and the Association for the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 Victims.

The Archives of Jeju 4∙3 include materials demonstrating the background of the historical event, as well as its outbreak and development. Also included are materials that document the history of collective damage suffered by the residents during the counterinsurgency operations. Additionally, the archives display the subsequent movement that the victims’ families and civil society continued in order to discover the truth and restore honor to the victims. The other items contained in the archives would be those related to the enactment of the Jeju 4∙3 Special Act, the process of institutional resolution based on public-civil cooperation, and the efforts made by the victimizers and the victimized for tolerance and harmony in order to surmount the conflict and confrontation. In this regard, the archives could be deemed a comprehensive set of records on relevant contemporary history, which spans from the time of the event to the present.

From a global perspective, Jeju 4∙3 is valuable in that it was a prelude to and an epitome of the Korean War, as the event was brought about by the Cold War and the division of the Korean Peninsula. The efforts to resolve the issues related to Jeju 4∙3 are also evaluated as an exemplary model of liquidating the past and achieving transitional justice in the mid-20th century. It presents a “vision for the future pursuing truth, reconciliation, coexistence, and peace,” going beyond the South African solution through “truth and reconciliation”; this is why many scholars and journalists around the world paid attention to the process of resolving Jeju 4∙3. The process also led to a range of events held in line with the global values of Jeju 4∙3, including the Jeju 4∙3 Peace Award, international academic conferences, and the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4∙3.

The value of Jeju 4∙3 is also recognized as a premise for the peaceful reunification of the Korean Peninsula. As the historical case was derived from the Cold War and national division, the two Koreas were divided again in perceiving Jeju 4∙3, failing to share a mutual understanding. The pursuit of national unification and self-governance of the community represent the values of peace when examining the historical characteristics of Jeju 4∙3; but this value has been damaged by the Korean War and the ensuing solidification of national division. However, the process of resolving Jeju 4∙3 and its message of peaceful unification, as shown in the incessant truth-finding movement on Jeju Island, Korea, fully manifests the value of the case’s peace-oriented nature.

2. Types of Archives of Jeju 4∙3

Largely, the Archives of Jeju 4∙3 consist of three parts. The first is a set of records related to the victims of Jeju 4∙3 (1947-1954), while the second contains the written records of victims’ imprisonments, deaths, disappearances, and/or injuries. The third part is related to the documentation of efforts made by victims’ families to discover the truth, restore honor to the victims, and practice tolerance and harmony.

The 4∙3 records are mainly composed of three parts. The first is a record related to the fact that there were victims during Jeju 4∙3 (1947-1954), the second is a record that describes the facts of the victims’ imprisonment, death, disappearance, and injury, and the third is a record which details the process of finding the truth, restoring honor, and practicing tolerance and harmony by the families of the victims after Jeju 4∙3`.

The archives contained in various media such as documents, photos, videos, and audio can largely be divided chronologically into those documents that were produced at the time of Jeju 4∙3 and those produced after. Documents from the time of Jeju 4∙3 include: government data, such as the minutes of Cabinet meetings — containing “the truth of the Cold War, national division, and collective victims”; materials from the military and police; materials from the civil armed forces; execution data such as national judgments and prisoners’ lists; data held by the United States, Russia, Japan, and other nations; and materials in the form of photographs and video images. Subsequent records produced while working to discover the truth include: the reports of the victims representing “justice, peace and human rights, and reconciliation and coexistence” (1,878 victims reported to the National Assembly, 14,343 to the Provincial Assembly, and 14,532 to the Jeju 4∙3 Committee); data about the campaign to discover the truth (held by the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute, the Joint Preparatory Committee for the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony, the Jeju Residents Alliance for Jeju 4·3, the Association of the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 Victims, etc.); the results of investigations by the Jeju 4·3 Committee (Jeju April 3rd Incident Investigation Report, written confirmation of victims, white paper, etc.); testimonial materials (held by the Jeju 4·3 Committee, the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute, MBC, etc.); data on the remains exhumed from secret burial sites; documents related to harmony (concerning the joint memorial services, the epitaph in the Yeongmowon memorial park, the reconciliation between victims’ families and police veterans, etc.); data on international exchange and cooperation related to Jeju 4·3 (with Taiwan, Okinawa, the United Nations, etc.); and private-sector materials (diaries, memoirs, essays, reports, etc.).

3. What is the Memory of the World Program?

UNESCO established the Memory of the World (MoW) Programme in 1992. The impetus came from a growing awareness of the precarious state of preservation of, and access to, documentary heritage in various parts of the world. Because the world’s documentary heritage belongs to everyone, the mission of the MoW Programme is to facilitate preservation and protection of documentary heritage for future generations, to assist universal access to it, and to increase awareness worldwide of its existence and significance.

The International Advisory Committee (IAC), the peak body responsible for advising UNESCO on the planning and implementation of the MoW Programme, met for the first time in 1993 to set the frame of the programme and create an action plan. The programme has inscribed the world’s documentary heritage on the MoW Register since the Memory of the World: Register General Guidelines to Safeguard Documentary Heritage was adopted at the 1995 UNESCO General Assembly.

All kinds of documentary heritage, corresponding to the selection criteria regarding world significance and outstanding universal value, are listed on the MoW Register following an IAC review, while technical support is provided for the preservation of, and access to, documentary heritage. With the selection criteria revised in 2002, the register now covers a broad range of media and means, not just literary documentation but also digitized resources such as visual documents, virtual documents, etc.

Documentary heritage is the information containing archives or the medium through which those archives are transmitted. It could be a stand-alone archive or archival fonds. It could also be materials that contain archives such as manuscripts, books, newspapers, posters in the form of paper, plastic, papyrus, parchment, palm leaves, bark, fibers, stones, or other materials. Non-textual materials such as drawings, prints, maps, and music are also included. All kinds of electronic data have also been added to the definition, including audiovisual images of historical or contemporary activities, original texts, and still images in analog or digital form.

The inclusion of documentary heritage on the MoW Register is determined through a review by the IAC in its biennial ordinary session when each member state is able to put forward up to two new nominations. In the Republic of Korea, the Cultural Heritage Administration submitted to the IAC ordinary session the application for two candidates selected through a preliminary application and review. To be inscribed on the MoW Register, the nomination should be important to the world. The IAC comprehensively assesses the documentary heritage against the criteria of integrity, authenticity (irreplaceability), significance, rarity, management plan, etc.

The procedures related to the MoW inscription were temporarily suspended from 2017 until finally resumed this year. There have been moves, mainly from the Japanese government, to fundamentally prevent the deliberation of controversial items, such as Documentation on “Comfort Women” and Japanese Army Discipline, attributed to the cause of being cautious about the politicization of UNESCO. There were other differences in positions between states, depending on their respective interests, regarding the order of the expert review and the method of disclosing the results of the review. Accordingly, UNESCO had discussions over said issues and has developed a new criterion for the MoW inscription.

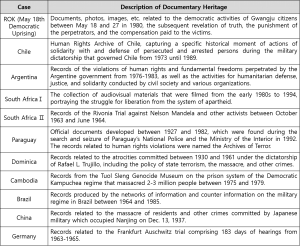

Currently, 428 nominations by 128 countries and eight organizations have been added to the MoW Register. Of them, sixteen items were submitted by the Republic of Korea, including The Hunmin Chongum Manuscript and The Annals of the Choson Dynasty. The following table shows the documentary heritage items related to contemporary history, inscribed on the MoW register, that pursue democracy, freedom, human rights, and peace as shown in the Archives of Jeju 4∙3.

4. Global value of the Archives of Jeju 4·3

The Archives of Jeju 4·3 include the materials that confirm the facts and damage related to victims that have “consistently” been recognized by the state. More than 70 years have passed since the outbreak of the historical event, and it is still used as evidence for trials and for deliberation and resolution by the Jeju 4·3 Committee. The archives will continue to be used as important data for the compensation and indemnification for the deceased and for the surviving victims.

In particular, detailed information on the damage to individual victims has been compiled through the report of victims to the National Assembly in the 1960s, to the local council in the 1990s, and to the Jeju 4∙3 Committee in the 2000s. Documents from public institutions that contain measures and orders taken by the government at the time of Jeju 4·3, as well as oral testimonies that supplementally confirm historical facts and damage are comprehensively and systematically collected. It can be said that such records are rare in that they have a very strong effect and influence. In the course of the war and the dictatorship in contemporary Korean history, a lot of data have been concealed, further increasing the rarity of existing data.

The Archives of Jeju 4·3 are comprehensive and conclusive records that have been collected in consideration of the time, the agent, and the purpose of their production. Given the continuous and systematic process of collecting the materials and the composition of the collected materials, it can be said that the Archives of Jeju 4·3 achieved completeness.

Those who hold the Archives of Jeju 4·3 vary, ranging from public institutions to private individuals. Currently, the documentary heritage items are dispersed and held by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, domestic and international archive institutions, private research institutes, and other Jeju 4·3-related groups such as the Association for the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 Victims, as well as private individuals.

The Archives of Jeju 4∙3 contain the records of a historical event caused due to the Cold War and national division of Korea. Jeju 4∙3 was analogous to, a prelude to, and an epitome of, the Korean War. From this global perspective, the Archives of Jeju 4∙3 contain the overall picture of the causes, development, results, and resolution of the crucial event. From a global point of view, the types and content of the records are very rich compared to those of other mass victimizations of residents by state authorities in other countries and regions. It is also important because records of over 15,000 victims have been well preserved. The Jeju April 3 Incident Investigation Report (2003) was developed by using the Archives of Jeju 4·3 as key sources and grounds. The investigation report was later translated and published in English, Chinese, and Japanese starting in 2014, enabling the global publicization of the truth of Jeju 4·3.

The Archives of Jeju 4·3 are a documentary heritage that contains the truth about the massacred victims and Jeju 4·3, a documentary heritage of reconciliation and coexistence for future generations, and a documentary heritage of solidarity and cooperation that contributes to world peace. The Archives of Jeju 4·3 need be inscribed on the MoW register so that its importance and meaning can be globally recognized. Through this, the archives should become more accessible, while used for education on peace and human rights, global citizenship, and democratic citizenship.

5. Future prospects and challenges

The Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation members witnessed the MoW inscription of Human Rights Documentary Heritage 1980 Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against the Military Regime, in Gwangju, Republic of Korea. This provided the foundation with the impetus to consider the inclusion of the documentary heritage items related to Jeju 4·3 because Jeju 4·3 and the May 18 Democratization Movement are similar in contemporary Korean history. In December 2012, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation hosted a debate by experts to open the discussion on the MoW inscription of documentary heritage related to Jeju 4·3. Subsequently, the administrative authorities of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province took the lead by designing the related project through opinion gathering, and in 2018, undertook the promotional project of including the Archives of Jeju 4·3 in the MoW Register.

The International MoW Programme was recently suspended due to the discussion on enhancing the practices in memory institutions. China’s Documents of Nanjing Massacre was added to the MoW Register in 2015. In 2017 when civic groups in Korea, China, and Japan submitted Documentation on “Comfort Women” and Japanese Army Discipline as a new nomination, the Japanese government demanded a reform of the practices in memory institutions, claiming that the UNESCO Programme is being used for political purposes. In April 2021, UNESCO finalized the bill on the reorganization of the MoW inscription system, which mainly stipulates that if there is a conflict of opinion between countries over the inscription of a documentary heritage item, a resolution shall be sought through bilateral dialogues and mediators, while the final decision on inscription shall made by the UNESCO Executive Board.

The Republic of Korea plans to submit in November this year its nomination forms for the documentary heritage items on the Donghak Peasant Revolution and the April 19 Pro-Democracy Movement, which underwent the 2017 deliberation process within the Cultural Heritage Administration. The next nomination period will be in 2023, for which South Korea’s candidates will be reviewed domestically in 2022. Therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly prepare to have the Archives of Jeju 4∙3 inscribed on the MoW register.

The expected MoW inscription of the Archives of Jeju 4·3 will help share the universal value of the reconciliation process of Jeju 4·3 with the world and give the Republic of Korea an opportunity to be globally recognized as a country with a mature sense of human rights. The successful inscription will also help the nation overcome the history of the Cold War, national division, a series of dictatorships, segmentation, and confrontation. The official global recognition that the reconciliation process pursued the values of truth, peace and human rights, and reconciliation and mutual existence is expected to eventually help resolve ideological conflicts as well as globalize the case example of Jeju 4·3.